|

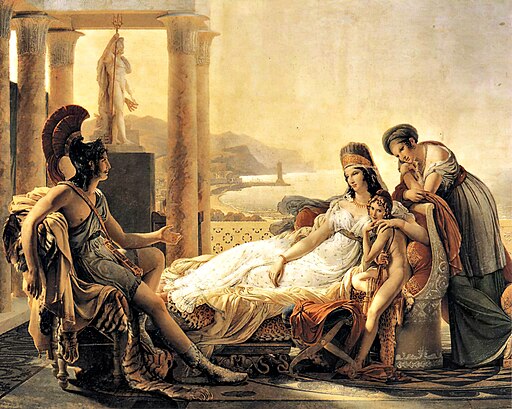

| Madonna of the Pinks Raphael, c. 1506-7 via Wikimedia Commons |

"Incomprehensible scheme! Oh! thou beautiful and wonderful Nature!—mother and moulder of the forms, and minds as well, of our wayward race. Now, she smiles in brilliant moonbeams on the grassy meadows, which wave with answering gladness to the whispering air. And the strong river flows as gently as an infant playing on the young mother's breast;—its murmurs as softly musical as that infant's voice!"

--January 1852 Scenes Beyond the Western BorderWhen the above was published, Philip St. George Cooke (1809-1895) was 42 years old. Ages of his four children with wife Rachel Wilt Hertzog Cooke (1807-1896):

John Rodgers (1833-1891): 18So Cooke's youngest child, his daughter Julia, was probably nine years old when the writer of Scenes Beyond the Western Border was moved to picture a young mother with her baby and compared the baby's voice to the sounds of a rippling river. Julia's mother was then 44.

Flora (1836-1923): 16

Maria Pendleton (1840-1926): 12

Julia Turner (1842-1902): 10

But Herman Melville's wife Elizabeth or "Lizzie" (1822-1906) had recently given birth to the couple's second child: second son (their first was Malcolm) Stanwix (1851-1886), born October 22, 1851.

Born June 13th (same birthday as PSGC!), Lizzie was 29.

Not long after, the July 1852 installment (likely composed in March-April) again refers metaphorically to an infant, this time one who is not happy but crying:

. . . the extra two miles over the lofty dividing ridge was terrible work for wagon mules; and it bruised I fear fatally a pet antelope fawn, which I had in a wagon:—it lies now in a neighboring tent uttering from time to time cries and moans which are distressingly similar to those of a suffering infant; said its soldier nurse, with real pathos, "it is thinking of its mother." I purchased another at the Fort; and a goat foster-mother.

--July 1852 Scenes Beyond the Western Border

Lizze experienced "a good deal of pain" and trouble while nursing Stanwix, as Hershel Parker describes:

But Stanwix's appetite [praised as "famous" by Maria his grandmother] was difficult to satisfy once Lizzie developed a breast infection. . . .

. . . the local physician, Dr. O. S. Root, advised her to continue nursing Stanwix from the left breast, despite the pain. The pain grew so severe that she decided she had to go to Boston to seek the help of the Shaw family physician, her uncle by marriage, Dr. George Hayward. --Herman Melville: A Biography V2.31-32Reporting on the follow-up in Boston, Laurie Robertson-Lorant explains:

Dr Hayward allowed her to continue nursing, but before long her right breast became clogged and the nipple cracked, causing her a great deal of pain. When the affliction persisted despite poulticing, he advised her to stop nursing.The next and last figurative reference in Scenes Beyond the Border to the musical "prattle of children" occurs in the August 1853 installment. Melville's wife Lizzie gave birth to their third child and first daughter Elizabeth (Bessie) on May 22, 1853.

--Melville: A Biography pp292-3

A gentle air rustles the grass or leaves; the running waters too, give music: and then, they seem the voices of gentle spirits, which may in this hour of calm and loveliness awake to Eden memories. As sometimes suddenly, the innocent prattle of children falls as music on the mother's ears, banishing happily, vexing cares,—so, nature now seems soothed, and harmony reigns. And as the mother, first musing in loving mood, then timidly questioning her happiness; —so too, to the eloquence of this sweet hour, my heart first beats a pleased response . . . . --August 1853 Scenes Beyond the Western BorderHere the maternal imagery seems partly influenced by lines addressed To the Young Mother in Mattie Griffith's Poems. Allusions to Eden also abound in Griffith's 1853 volume. Kind of amazingly (how did I miss this before?), our manly Captain of U. S. Dragoons is once again feeling like a woman--comparing his own tranquilized emotions to those of a pondering mother soothed by the audible presence of her children.